phrase

The activities and experiences that constitute a person's normal existence.

- ‘The way you experience your daily life will hinder your ability to cope.’

- ‘It is true that people take their cues from what they see and experience in daily life.’

- ‘This summary of body image accords with the common experiences of daily life.’

- ‘There are also few new experiences for you, just the humdrum of daily life and the loneliness of having to get on with it on your own.’

- ‘Sometimes you step back from your routines of daily life and think about your life as a whole.’

- ‘I think a central space should be designed for daily life, not for special events.’

- ‘Sharon grew up in an area where musicianship and song are integral facets of daily life.’

- ‘Gambling is a fundamental part of human nature - we all take risks in daily life.’

- ‘It's more a story about problems within us and dealing with daily life in a city like this.’

- ‘When was the last time you applied what you purport to believe in to your daily life?’

Iroquois Nursing Home Inc started providing nursing home service since Nov 4th, 1992, and was recognized by Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) as one of modern providers which are carefully measured and assessed to have high-quality nursing home services for promoting health and improving the quality of life. Iroquois Nursing Home. Your favorite soft, relaxing music now has a new address. Here's where you'll find Streisand, Manilow, Diamond. And all the songs you've missed from the singers you love. WLYF-HD2. ©2017 Entercom Communications Corp.

Dream Practices in Native American Cultures

A small bit of the research I’ve done on dream theory. Enjoy (:

Dream Practices in Native American Cultures

All humans dream every night. However, it is the norms of each person’s cultural upbringing and surrounding society that determines how an individual reacts to and interprets these dreams. As Lee Irwin reminds us, “We all dream…if we forget or do not attend to our dreams, the images and activities that come to us unbidden, it is because our cultural environment does not support a means by which dreaming could transform and revitalize our awareness” (Irwin, 9). Western cultures are primarily ruled by logic and reason, and theories about dream interpretation have been isolated to fields of psychology. Mainstream western religion and society disregards dreams as fantasy or nonsense. Other cultures, especially Native American cultures, have a contrary perspective. Dreams and visions hold an essential role in the religious, historical, and storytelling traditions of Native American tribes across North America. In this paper, I will explore the role of dreams in the Eastern Woodlands and Great Plains Native tribes of North America. I will illuminate how these tribes utilize their dreams to connect to the land on which they live, to explore personal experience, and to communicate through community performance.

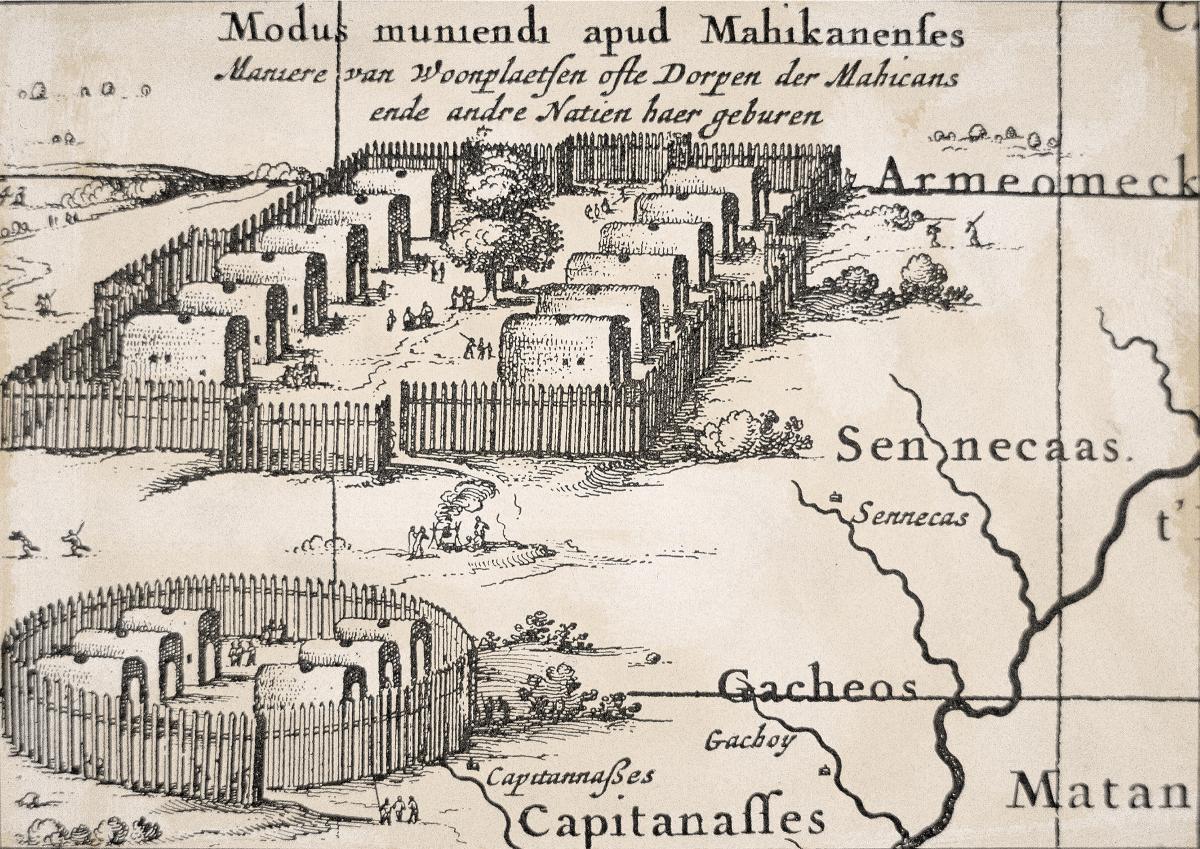

Dreams are viewed as a core aspect of Native American culture. In traditional Iroquois families in the Eastern Woodlands, parents encourage children to recall their dreams each morning to promote habitually paying attention to and valuing them. The dreams are interpreted to have real life consequences. Sometimes, dreams can be purposefully misleading to propose a challenge to the dreamer, but other times, they hold answers to real life concerns. (Tooker, 90). In the traditions of the Great Plains tribes, no distinction is drawn between physical, waking reality and the reality of dreams and visions. Dreams are instead just another medium through which a person can experience and perceive the multitudinous layers of reality. These realities are “enfolded” into one another in layering realms of perception. Neither physical reality, nor dream realities are considered more or less real than one other (Irwin, 18). That being said, the information and power transferred into experienced dreamers through dreams and visions are highly valued and respected both socially and religiously: “Among traditional Plains peoples, dreaming is given strong ontological priority and is regarded as a primary source of knowledge and power” (Irwin, 19). The information and perceptions acquired during dreams surpass the level of experience available in everyday perception, and therefore, skilled dreamers are perceived to have great amounts of power.

The imagery and information of dreams are used to tie the Native Americans to their land. This is a very intriguing process, as a nearly subconscious function of the mind is used to connect to the extremely physical reality of the earth. In daily life, Iroquois people use dreams for logical purposes in navigating the land, such as to hunt game (Tooker, 91). The Iroquois also incorporate the telling of their dreams into the celebrations of crops throughout the different seasons. During celebrations such as the Green Corn Ceremony, Maple Ceremony and Strawberry Ceremony, traditional dream songs are retold to celebrate the rebirth of nature. Any participant in the ceremony who has a vision—a dream-like experience while being awake—communicates what they learned through performance and ritual. This information is used immediately to improve daily life, perhaps by enhancing the harvest or aiding the sick (Tooker, 269).

It is worth considering that westerners write most information available about Native American traditions. When the western settlers took over the native land, they proposed a very different method of recalling and recording history: written text. Traditionally, the histories of the Native Americans are told orally, through the passing on of stories, dreams and visions. In this way, the dreams of the people become an integral part of the identity of the tribe, as the experiences become a part of their history: “The Anishinaabe heard stories in their dream songs. Tribal visions were natural sources of intuition and identities, and some tribal visions were spiritual transmigrations that inspired the lost and lonesome souls of the woodland to be healed” (Vizenor, 9).

Gerald Vizenor offers a firsthand perspective of an Anishinaabe native in Summer in the Spring. In this book, Vizenor undertakes the project of translating a collection of Anishinaabe dream songs not only into English, but also into text. Dream songs are traditionally passed down from generation to generation via speech and song. Oral transmission allows stories to adapt over time and space. As a result, the stories are continuously relevant to current issues and practices. Text, on the other hand, freezes a story at one specific moment in time. Oral language can also use intonations and gestures in ways that punctuation cannot compare to: “The use of italicization and lower case for anishinaabemowin words is intended to emphasize the value of oral language rather than a total imposition of the philosophies of grammar and translation” (Vizenor, 19-20). Thus, writing dream songs in a book is not only a translation from anishinaabemowin into English, but also a translation from native cultural traditions to western cultural traditions.

The book Summer in the Spring is a collection of dream songs. Dream songs are pieces of knowledge given to a dreaming individual by their dream-spirit. The dream songs in Summer in the Spring tell stories of Anishinaabe connections to nature and the land through the character of the “trickster.” The collection is rich with nature imagery:

“as my eyes

look across the prairie

I feel the summer

in the spring” (Vizenor, 23).

The dream songs capture the essence of the native land as it is experienced through physical and dream perceptions. This book allows the collective memories of the Anishinaabe people to live on even once the land’s ownership has turned over to western settlers.

It is important to remember that Native Americans do not have different dreaming abilities than westerners. Rather, they just interact with their experiences in a different light. The natives of the Great Planes use the imagery of their dreams to link the dream realms to the physical world in which they live: “There is a strong sense of continuum between human perception, the natural world, and the mysterious appearance of visionary events…a stone might speak, an animal change into another creature, a star fall to earth as a beautiful woman” (Irwin, 27). These transformations and personifications are the same sort of phenomena that occur in all human dreams. However, it is the mode of interpretation that alters the significance. Rather than disregarding these transformations as irrational and unimportant, the Native Americans use them to personify their world and relate to the earth more fundamentally. Hearing a stone speak in a dream alters the dreamer’s encounters with stones the next day, as he or she has gained insight into another mode of perception of the same object.

The Native American focus on the dream experience opens up possibilities for personal awareness: “The dream is a medium of knowing, a way of experiencing the reality of the lived world, a faculty of perception” (Irwin, 21). To incite the experience of a vision, natives of the Great Planes strive to earn the compassion of a dream-spirit who will guide the dreamer through his or her vision. Compassion and pity for suffering draws the dream-spirits to the dreamers. In order to acquire this sympathetic attention, dreamers would often fast, cut off pieces of their own flesh, and cry. Even the most powerful and strong men would weaken themselves in order to be granted a vision: “The vision seeker’s lamentations and emotional expression are cathartic of deep feelings of dependence and conditionality” (Irwin, 139). Women were more likely to have these visions, since they were more likely to experience strong, deep-rooted emotions.

The cathartic emotional release of weakening the self results in the much-valued visions, or waking dreams. The dream-spirits are drawn to the obedience and suffering of the dreamers, and then aid the dreamer in discovering knowledge and power in his or her visions. Expressing dependence on the spirits encourages them to give the gift of power to the dream seeker. Once the vision begins, a mysterious animal known as an icha’eche transfers power into the dream seeker (Irwin, 140). The resulting visions are “highly imaginistic, nonverbal, spatially defined, and emotionally laden,” unique to the individual and his or her emotions, perceptions and needs (Irwin, 16). The dream songs that are given to the dreamer by his or her dream-spirit are meant to be taken at face value: “Dream songs are of private revelatory nature; words of power are not to be discussed or debated, only used to invoke their sources” (Irwin, 165).

An advanced dreamer no longer needs to incite the help of the dream-spirit, but rather, can enter and exit the visionary world at will in a “dramatic demonstration of power and ability” (Irwin, 22). Thus, the “power” acquired from the dream-spirit in order to incite a vision is directly related to the social power an individual has within their own tribe. Practiced dreamers often incite their visions at ceremonies and rituals as a form of community performance: “The explicit cultural order of religious symbols, icons, rituals, dances and songs represents a testimony to some sort of received, inherited, or purchased power, frequently transmitted through dream experience” (Irwin, 25). At such rituals, the vision is not translated or interpreted for the onlookers. Rather, the symbolic gestures, actions, words and songs expressed by the dreamer are left to speak for themselves in a performance of power and knowledge. The dreamer communicates the message of the dream to the community while still keeping the details of the experience mysterious. This assures that the dreamer maintains the power to interpret the dream, as they are the only one to experience it firsthand (Irwin, 165).

Dreams play an essential role in telling the communal story of the tribe. The individual recollections of experience are performed and retold until they turn into a collective history that runs throughout the culture and traditions: “the unique psychic history of the individual also contributes a memorable testimony to the collective identity of a people” (Irwin, 164). Through their dreams, each individual contributes directly to the collective history and culture of the tribe. The experience of dreams and visions are mediums of communication inseparable from the physical environment. Each dreamer’s experience and practice are woven into the religion, culture, and beliefs about the land, personal reality and power (Irwin, 26). The dreams are viewed as a communal activity that links the culture between the dream experience and the waking lives of the members of the society.

Native Americans are the original owners of the land on which United States citizens now dwell. Native American connections to the land, to each other, and to themselves are deeply rooted in an attention to their dreams and visions. Dreams help to enhance individual ties to his or her homeland. The individual experience of dreaming flourishes knowledge of the self. The performance of dream songs and visions at rituals and ceremonies engages the community in a communal knowledge and history. There is much to learn from studying these practices and reading these dream songs. However, the western scholar must not forget that they too have the ability to dream every night, and experience the same phenomena that the original owners of the land deemed sacred and powerful. Social standards and cultural traditions are the only distinguishing factor between a disregarded dream and a sacred vision. Learning from the beliefs of other cultures can help enhance our understanding of our selves as individuals, human beings, and members of the earth.

Works Cited:

Irwin, Lee. The Dream Seekers: Native American Visionary Traditions of the Great

Plains. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1994.

Tooker, Elisabeth. Native North American Spirituality of the Eastern Woodlands:

Daily Life Iroquois Facts

Sacred Myths, Dreams, Visions, Speeches, Healing Formulas, Rituals, and

Ceremonials. Mahwah: Paulist Press, 1979.

Daily Life Iroquois

Vizenor, Gerald R. Summer in the Spring: Anishinaabe Lyric Poems and Stories.

Daily Life Iroquois

Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1993.